KOSMOpolita

Basque Artists Make Their Mark in the Big Apple

2004/01/23-30 Basque Artists Make Their Mark in the Big Apple Gloria Totoricag?ena, Center for Basque Studies. University of Nevada, Reno

Art does not necessarily satisfy a desire in the listener or viewer, rather, it creates it. The ingenuity of expression by Basques in New York extends on through dance, musical instruments, and vocalists, to representative artistry of sketching, painting, sculpting, engraving, directing cinema, and writing literature. From 1946-48, an all-Basque language cultural review of literature, art, and music, named Argia, or Light was published in New York. It educated and informed the city’s Basques regarding the latest trends in Euskal Herria as well as in other countries, and is one of the few examples of early media published in Euskara in the United States. Basques in New York City are the beneficiaries of more than a century of community activities, which in addition to politics, cuisine, music and dance, have also included access to art exhibitions, displays, and workshops.

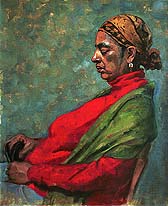

Basque immigrants, regardless of their host community in over twenty countries, tend to decorate their homes with ethnic artistic representations, such as New Yorker Iñaki Astondoa’s “Pamplona room” where he exhibits a painting of his hometown, Lily Aguirre Fradua’s living room painting of Bakio, or Gabrielle Amestoy’s painting of her family farmstead from Macaye. It is common to find carved wooden busts representing a traditional Basque Amuma, or grandmother, and Aitxitxe, or grandfather in places of honor in family living rooms. Sketches of a Basque countryside, and photography of traditional symbols such the Tree of Gernika, are common in Basque households. Basques in the diaspora tend to try to surround themselves, or at least display a few objects, that remind themselves of “home”. Though traditional representational art is more common with Basques in New York for home and office display, the art being produced currently by the Basques in this cultural capital is anything but traditional. Amaia Gurpide Rubio (Figure study).

The New York Basque community has always valued art, beginning with the Basque painter Félix de Echevarria’s exhibited paintings in Manhattan museums and his oil paintings and murals on the walls of the Valentín Aguirre Jai-Alai Restaurant, operated between the 1920-1950s. Maria de Landaburu, owned and operated a bookstore at 11 Cruz Street where she also exhibited Basque artwork, and her son, Juan Kunzler Landaburu, collected Basque art and held private showings at his residence. Both worked to promote Basque artists to the greater New York society. C. Alonso Irigoyen and his wife, Inga Lindgren, were high society aristocrats and collaborated with, and contributed to, many benefits and charitable projects in the art world in the 1950s and 1960s. They auctioned off several pieces of privately owned artwork valuing more than $200,000 which is a significant amount today, and was of course even more substantial in 1960.

José-Maria Cundin, born in Getxo, Bizkaia in 1938, is known and esteemed as an outstanding advocate of the historical 'Avant-Garde' of the Basque Country. His first immigration was to Bogotá, Colombia, where he lived during the 1950s and where he created wide-ranging projects that were favorably received in the Colombian art world and greater society. Cundin established his residence in the United States in 1958 in New York. He created political vignettes and illustrations in New York for publications such as Bohemia Libre, Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas, and the Editorial Sudamericana. In 1958, he established the popular New York Itinerant Puppet Theatre. In 1964, he moved to New Orleans where he was regarded with renown and his works are still part of several gallery permanent collections. Presently he resides in Annapolis, Maryland where he is an Artist in Residence at the Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts. Cundin's paintings and sculptures are in numerous private collections in Europe and the Americas and his works are displayed in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao; the Museo de Bellas Artes de Vitoria-Gasteiz; the Museo de Zea, in Medellin, Colombia; and the New Orleans Museum of Art at Johnson & Wales University. Amaia Gurpide Rubio (Mercedes).

Cundin has created an engraving of “The Unanimous Declaration,” regarding the Declaration of Independence of the British colonies in North America. This is the first engraving by hand which has been created, produced, and released during the last one hundred and fifty years. The Millennia Edition of the “Declaration of Independence” was carved by hand on a brass plate by Pedro Maria Azpiazu, a Basque artisan, who is considered to be among the finest metal engravers in the world today. The paper used for this production was especially formulated and hand made by Villabona, a papermaker in Euskal Herria. The printer is Arturo Garcia, director of the renowned Taller Mayor of Madrid. Artist Francisco Cabezón Castillo, of Bilbao, was invited to New York to produce a one-man show of his paintings in 1976. His style is called “Rhythmic Expressionistic”, and he exhibited at Georgetown University in Washington D.C., Alfred University in Rochester, New York, and at Montgomery College, and the Cleveland Galleries in Maryland. Ana Mendieta, a Basque from Cuba, earned a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1980 and moved to New York to develop her artistic skills. Her creations, which came from earthworks suggesting human forms, were represented in a number of exhibitions including the Kouros Gallery on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. Amaia Gurpide demonstrating wine drinking at exhibition.

More recently, Amaia Gurpide Rubio, born in 1974 in Pamplona migrated to New York in 1999. She began her studies in the Art School of Pamplona in 1990, and by chance one day, she met one of her former art teachers, Mikel Esparza, who had been in New York for thirteen years. “And I decided I could do it too,” she said. “My teacher was the biggest influence for me to come to New York in 1999.” Gúrpide began to study and work in the National Academy of Science, and continues there in 2003. She won the Allied Artists Award for her piece, "The Harvey Dinnerstein Class Concert," and she continues her expression in sculpture, drawing and engraving. Nisa Goiburu.

The inaugural reception of the launching of the project of the Basque International Cultural Center at the Seamen’s Church Institute near the South Street Seaport in Manhattan, featured twelve paintings of Nisa Goiburu. The plans for this Cultural Center are for Basque artists to have their own permanent gallery, which will exhibit homeland artists, and Basque artists from around the world, in a highly visible and high traffic area in lower Manhattan near Wall Street and the former World Trade Center. Goiburu’s works were presented here as an example of the high quality of Basque produced artistic expression in New York, which needs a public venue for exhibition. Several other Goiburu works, such as “Hitz Entzuten”, Listening to the Word, were also exhibited in 1999 at the Caelum Gallery in New York.

Anita Glesta has always felt a special and unexplainable connection to the Basque people. While she is not ancestrally Basque, she is “intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually Basque.” Glesta lived in the Basque Country for one year as a teenager, and that period of time transformed her life. She has worked tirelessly in the New York art community in the area of public art, and has suggested to the City of New York that the Twin Towers Memorial include a seedling of the Tree of Gernika as a symbol of the hostile targeting of innocent civilians. She has presented a proposal for public art in the Basque Country that includes a walking path through Bizkaia with monument commemorations of Basque victimization in various wars and during the Franco dictatorship. Casa Alzogorea watercolor painting by Amaia Gurpide.

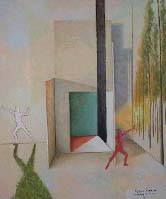

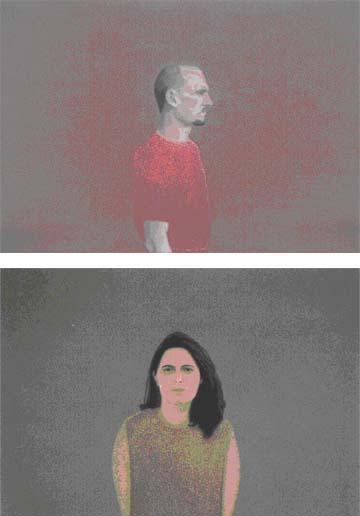

Guillermo Zubiaga creates his own personalized Christmas cards each year for friends and family, using guash, an opaque watercolor. He has a great interest in Basque mythology, and because of the repression of the oral culture in the Basque Country and the scant transmission of mythology, his interest in art intensified. He said, “There are very few Basque myths that are written and published in the Basque Country, and because of the renaissance more books are being published. “I think we have to tell our stories because they belong to us as Basques. I think there is a market for that, and even if not, it is part of my identity and I want to do it symbolically.” Born in Baracaldo, Bizkaia in 1972, Zubiaga migrated to New York in 1993, at twenty-one years old, lived with his brother briefly until his brother returned to the Basque Country, and “was left by myself, and I didn’t know a single person in this huge city,” he said. He studied in Syracuse and gained employment in 1994 drawing animations. Later he worked in a Manhattan café that was also an art gallery, and in 1997 met a person with connections in the comic book and animations industry. Zubiaga draws illustrations for comic books, and teaches two art history courses. “I love commercial art, but it’s very competitive, just like everything else in New York,” he said. Iñaki Lazcoz. Iñaki Lazcoz.

Iñaki Lazcoz is another artist born in Pamplona in 1973, who then studied Fine Arts at the Euskal Herriko Uniberstitatea, University of the Basque Country, in Leioa, Bizkaia. He graduated in 1996 and moved for four years to live, and to paint, in Vienna. Lazcoz explained his professional development, “I applied for an international contest organized by Art Link from Israel, it was international young art in collaboration with Sotheby’s. I saw a pamphlet that had the information, and I just applied for fun; I never thought I could be chosen.” His winning work was auctioned in Israel and in New York, and when he came to the New York auction, he met up with Amaia Gúrpide Rubio,his old friend from school in Pamplona. The Basque art information network worked well enough to have him stay in New York, creating portraits of persons, objects, and animals into large, out of context backgrounds. “My work makes people think and reflect, you can look at it for a long time, you need time to look at it. It is deep. I have a unique style, and I was an island in my class because most other people were painting expressionism and other known things, but I was not,” said Lazcoz. Iñaki Lazcoz. This general smattering of information regarding Basque artists in New York exemplifies the contemporary immigration by those who have transplanted themselves to the international center of culture. Generally, they have arrived with university level training and often also with professional qualifications, some knowledge of English. They have migrated for personal fulfillment issues, and not necessarily out of economic hardship or political exile. When the New York Film Festival of 2001 and the “Spanish Cinema Now” festival at the Walter Reade Theater collaborated with the Instituto Cervantes of New York to feature Basque directors such as the Navarrese Montxo Armendariz, Basques in New York were not surprised. When the Basque International Cultural Center newsletters mention a need to exhibit artwork of Basques, they mean it as a permanent function. This is a marked difference between the Basques of New York and those of the west coast. New York Basques are surrounded by globalized culture, and with the cultures of the entire globe. Basque identity, and definitions of “Basqueness” are much more varied than the traditional symbols and Spanish Civil War Republican hymns common in the American West Basque communities. In addition to –and definitely not in place of- traditional Basque culture of the 1900s to 1940s, the Basque community in New York also has access to contemporary manifestations of Basque culture, including Basque punk rock, Basque poetry readings, Basque cinematography, Basque literature, etc. They add these as additional layers of Basque identity and Basque culture. Earlier version presented in: Totoricag?ena, Gloria. The Basques of New York: A Cosmopolitan Experience. Serie Urazandi. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Eusko Jaurlaritza. 2003.