KOSMOpolita

Consent and descent relations in contemporary Basque American literature

UPV/EHU

Monique Urza, The Deep Blue Memory (1993)

Robert Laxalt Alpetche. T he present article deals with family bonds as one of the most recurrent themes in contemporary Basque American literature, with an emphasis on the interaction between descent relations and consent relations in Basque immigrant families in the American West. In fact, the leading Basque American writers of the last few decades, including Robert Laxalt (1923-2001), the most accomplished literary interpreter of the Basques in the United States, have often focused on the tension between loyalty to family ties and the individual’s search for his/her own individuality.

Any discussion of the role of family ties in contemporary Basque American literature should inevitably begin with an analysis of Robert Laxalt’s Basque-family trilogy. In fact, after the impressive success of Sweet Promised Land (1957), the book that put an end to the literary invisibility of the Basque immigrants in America, Laxalt confirmed his position as the literary interpreter of the Basque American community with his semiautobiographical trilogy of the Indart family, composed of the novels The Basque Hotel (1989), Child of the Holy Ghost (1992), and The Governor's Mansion (1994). This trilogy is basically the story of a Basque immigrant family in the American West told by a second-generation son, Pete Indart. In Laxalt's trilogy family becomes the main common thread of the three volumes. These novels offer different perspectives on family relations in a Basque household, but they all stress the tension between the power of family ties and the individual's desire to develop his own personality. Or, to use Werner Sollors' terminology (Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in America, 1986), we can view Laxalt's trilogy as an exploration of the tensions between "descent" and "consent", between ancestral or hereditary bonds and self-made or contractual identity (see also D. Río, Robert Laxalt: La voz de los vascos en la literatura norteamericana, 2002). Robert Laxalt Alpetche.

In the first volume of the Indart saga, The Basque Hotel, its protagonist, Pete, undergoes a process of change from innocence to experience. This initiation process also transforms gradually his attitude to his Basque heritage. Thus, Pete's journey from childhood to adulthood is also a journey from ethnic ignorance to ethnic awareness. However, Laxalt does not mean that this character is headed for a total identification with his ethnic heritage or his family ways. In fact, as he grows up, Pete experiences a process of individuation, of psychological separation from the family.

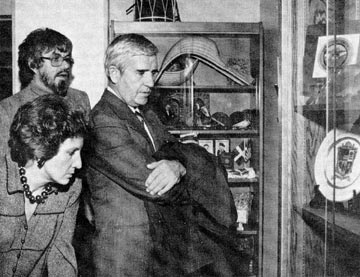

In Child of the Holy Ghost Laxalt resorts to the same narrator, now a grown-up, to explore the Basque heritage of this immigrant family. The most remarkable sections of the novel are the ones devoted to exploring the peculiar circumstances of the birth and upbringing of Pete's mother. Laxalt emphasizes the ancestral relevance of family bonds in the Basque Country in the early twentieth century. However, he also uses the fact of illegitimacy and its painful consequences for both the grandmother and the mother of the narrator to illustrate the preeminence of respectability above blood relationships in traditional Basque families. Paul Laxalt Alpetche and his wife visiting the Basque Studies Program of the university of Nevada.

In The Governor's Mansion, Laxalt employs a modern American setting to explore the impact of politics on the same tradition-bound immigrant family. The main sources for the book are actual political events experienced by the author assisting his brother Paul Laxalt, former Nevada Governor and U. S. Senator. Laxalt portrays the Indart family as a closely knit unit where each of its members contribute to the well-being of the others. Nevertheless, Laxalt also hints in The Governor’s Mansion that the sacred circle of family may work as an obstacle to the individual's personal development.

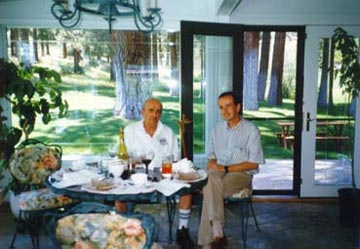

Another Nevada novelist, Frank Bergon, has also written insightful portraits of the role of family bonds among Basque immigrants in the American West. In his first novel, Shoshone Mike (1987), one of the main characters is Jean Erramouspe, the son of a Basque sheepman murdered by a group of Shoshones. Bergon focuses on Jean’s inability to come to terms with his family and ethnic legacy. In fact, Bergon utilizes Jean Erramouspe to show the extension of prejudice and discrimination against the Basques in the American West in the early twentieth century. The Basque presence in the American West also plays a prominent role in Bergon’s third novel, Wild Game (1995). Its protagonist is a contemporary Basque American, Jack Irigaray, a game warden whose conflictive relation with his Basque heritage Bergon examines in detail. In this novel Bergon also underscores the transformation of the Basque American communities in the West. For example, the traditional unity of the Basque family is no longer taken for granted in the new generations, as illustrated by Irigaray’s failure as a husband and his divorce from Beth. Robert Laxalt and David Río at Bob's house near Carsan City, Nevada.

Another relevant Basque American novelist in Nevada fiction is Monique Laxalt Urza, Robert Laxalt’s daughter. In her semiautobiographical novel The Deep Blue Memory (1993) Urza resorts to a female perspective to portray the conflict between loyalty to one's ethnic heritage and Americanization. In this book Urza examines the complexity of the immigration process through different generations of the same family. Although Urza's novel may be viewed as a celebration of the power of the immigrant family and of loyalty to its heritage, The Deep Blue Memory also emphasizes the importance of consent-based relations for the proper development as individuals of the descendants of immigrants. In fact, the unity of the Basque family has to compete in the novel with the traditional American devotion to the individual's personal features. Thus, the book reveals the potential damage of an overemphasis on the family, on descent relations (see D. Río, “Monique Laxalt: A Literary Interpreter for the New Generations of Basque Americans”, 2003).

Among the newest generation of Basque American writers, the most relevant voices are those of Gregory Martin and Martin Etchart. Gregory Martin is the author of Mountain City (2000), a highly acclaimed memoir on the everyday life of a small community in rural Nevada, with a particular emphasis on Martin’s Basque American family. The book records powerfully a sense of place and highlights Martin’s learning process from his grandparents: “They’re teaching me how to grow old” (169).

Martin Etchart is a third-generation Basque American, born and raised in Arizona. He is the author of The Good Oak (2005), a masterful “Bildungsroman” where the value of family ties is enhanced. The novel, based on Etchart’s personal memories of his own youth, follows a grandfather and his thirteen-year-old grandson on a sheep drive from Phoenix into northern Arizona mountains. Throughout the journey, both of their lives are changed, but especially the grandson’s. In fact, Matt Etchbar, the adolescent protagonist, develops a new bond with his grandfather, and he learns also about the value of coming to terms with his Basque heritage. In general, the novel celebrates the power and rewards of family for the descendants of immigrants, and also the need to accept their ethnic heritage for their proper development as individuals.

All the different books mentioned throughout this article illustrate the pivotal role played by family bonds in contemporary Basque American literature. Certainly, their authors do not share a common perspective (actually, there are different generational and even gendered approaches) and besides the emphasis on descent-based relations often coexist with the recognition of the importance of consent-based relations in Basque immigrant communities. However, in most of these books family awareness becomes a fundamental element to understand the legacy of Basque heritage in America. WORKS CITED Bergon, Frank 1987: Shoshone Mike. New York: Viking. ----------------- 1995: Wild Game. Reno: U. of Nevada P. Etchart, Martin 2005: The Good Oak. Reno: U. of Nevada P. Laxalt, Robert 1957: Sweet Promised Land. New York: Harper. ------------------1989: The Basque Hotel. Reno & Las Vegas: U. of Nevada P. ------------------1992: Child of the Holy Ghost. Reno, Las Vegas & London: U. of Nevada P. ------------------1994: The Governor's Mansion. Reno, Las Vegas & London: U. of Nevada P. Martin, Gregory 2000: Mountain City. New York: North Point P. Rio, David 2002: Robert Laxalt: la voz de los vascos en la literatura norteamericana. Bilbao: U. País Vasco. ------------- 2003: “Monique Laxalt: A Literary Interpreter for the New Generations of Basque Americans”. In Linda White and Cameron Watson, eds., Amatxi, Amuma, Amona: Writings in Honor of Basque Women. Reno: Center for Basque Studies (U. of Nevada, Reno). 86-98. Sollors, Werner 1986: Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture. New York & Oxford: Oxford U. P. Urza (Laxalt), Monique 1993: The Deep Blue Memory. Reno: U. of Nevada P.