Gaiak

The hidden manuscript. Reality, delusions and movies in the siege of the San Sebastián International Film Festival (1862-1905)

CHAARANI, Naoufal RILOVA JERICO, Carlos

This week it is a good, proper, time, to talk here about cinema. The reason?, it is simple: as every year, the city of San Sebastian celebrates its increasingly worlwide famous film festival.

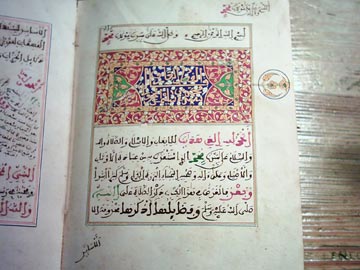

Le retour de Martin Guerre, superbly directed by Daniel Vigne in the year 1982, should be a good step to start an article like this one. That wondrous reconstruction of sixteenth century french peasant life was based upon one of the most interesting books of History written during the last century. In its last pages the author, the historian Natalie Zemon Davies, remembered the words of a young mother newcomer to Artigat, the village were that historical drama took place. The girl told to a neighbour who was walking by her side that Artigat was a calm, perhaps boring, place. Nothing interesting happened there? The woman answered that maybe not today, but in the sixteenth century one day appeared a man who told everybody he was the real Martin Guerre, the one who run from the village more than ten years ago… Then the neighbour narrated her the story of the fake Martin Guerre and the true one, who returned just in time. A thrilling tale wich was “translated” to images two different times. The first by the aforementioned Daniel Vigne and the second by Jon Amiel in 1993, who transformed Artigat into a southern village during the hard times of the Reconstruction period and Martin Guerre into a certain Jack Sommersby. The Tamsammani manuscript. San Sebastian city library.

The main part of the inhabitants of the bourgeois, conventional and relatively calm city siege of the International Film Festival should ask the same question proposed by the young mother of Artigat: nothing amusing happened in San Sebastian?, the unique “interesting things” we can remember, appear only in the images of the movies that visit the city each year?

The answer, surprisingly, should be the same offered to the young newcomer by the peasant woman of Artigat. Perhaps not today, but in the sixties of the nineteenth century…

During those years San Sebastian, and specially one of its more prominent citizens, were experiencing the beginning of historical facts that, a hundred years after, became, as the story of Martin Guerre, a movie. Page of the Tamsammani manuscript. San Sebastian city library.

Indeed, it is not the first time that this magazine talks about Fermín Lasala y Collado, duke of Mandas. Months ago we learned here that the young millionaire was one of the tycoons who built up the United States railroad net as a part of his huge business. That fact, interesting -and unknown- as it was, it is not the last surprise he kept in his private archives (fortunately donated to the guipuzcoan Diputacion to instruct, and to amaze, us today), and, also, among the 14.000 volumes of his library donated -with his most important manor, Cristina-enea- to the town council of San Sebastian.

The city archives reveal, indeed, a first clue on some amazing facts. There we can find a complete list of his books. In its last pages appears a note that talks about a valuable arab manuscript… Page 119 of Tamsammani manuscript letter by the copist. San Sebastian city library.

Then, are we, at last, before an exotic mistery? It is obvious that the two aldermen who made the list in the year 1918 did not know a single word of arab. They could not even guess the manuscript´s title. The only thing sure to them was that they were before an evidently valuable item, perhaps written in the XVth century. But, as long as they knew, it should be the complete works of Avicena or that infamous Necronomicon cast as a myth in these years by an still unknown Howard Phillips Lovecraft.

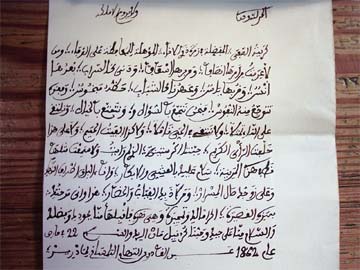

A few years after somebody decided to translate partially the misterious book. So, he consulted an expert of “Al-Andalus” magazine, the paper of the spanish arabists. Light shined at last upon the mansucript. It was not a medieval relic but a luxurious replica of some arab classical texts made in the year 1856 by a famous tangerine copist, Muhammad ben al Hayy Muhammad al-Tamsamanni. The contents of the not so misterious manuscript were, apparently, something less than original: a prayer book, the “Dalavil al-jayrat”, wrote in the year 1472 A. C. by Muhammad ben Sulayman al Yazuli and a Decameron of tales, legends, charades and some philosophical reflections upon the most different subjects: the beauty of the bride, the treason, the friendship... Page 167 of Tansammani manuscript letter by the coronel. San Sebastian city library.

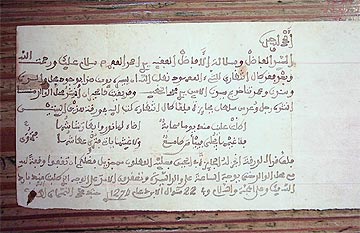

Ángel González Palencia, the secretary of “Al-Andalus”, sent a really correct inform to the city library, but there was something more under that quiet surface… Evidently the philologist did not know nothing about Fermin Lasala y Collado except he was the former owner of the Tamsamanni manuscript. Then, he never asked himself about the letter sent with the book to the duke by a certain colonel Man-e-rik -probably a boutade among old friends to disguise the correspondent´s true surname: Manrique- and its contents. And this was, precisely, the key that take us directly to the core of that story wich John Milius transfigurated into a movie entitled “The wind and the lion” in the year 1975.

Indeed, Ángel González Palencia translated the letter superficially: that little sheet told something about a lady called Cristina, the most beautiful woman in Madrid and other polite expressions like that. Nevertheless a deeper reading of this document reveals that the colonel “Man-e-rik”, a man very well learned in arab literature, acted like one of those characteristic “jeweller of words” -excellently portrayed by some european historians as Charles Pellat- and flattered Cristina with his brighting imitation of the arab poetic prose. So then, she is the favourite of the fashionable society of Madrid, her commands are lawful and the colonel submits himself to them happily. Be by her side it is relief and her figure is as delicious as a mirage; she brights like an estatue upon the water, her brow and her face are unparalleled in Madrid… and so on.

Wich was the final purpose of all that honest -as the author confessed- praise?, another joke among old friends like the colonel and the duke seemed to be? Maybe, but the manuscript, and specially the letter, as any other historical documents, have an exact context and there, as usual, should be the answer to these questions.

Portrait of Fermin Lasala as ambassador. San Sebastian city museum. The letter was wrote on 22th march of the year 1862. And that it is, perhaps, a really important fact to learn about how and why that strange manuscript reached the hands of Fermín Lasala y Collado. There are two probable explanations.

Let´s consider the first one. That year Spain was master of a great part of Morocco. One more time the weak alaui empire, as usual after the eighteenth century, could not defeat the european armies -mainly spanish- that periodically invaded its homeland.

That colonialist adventure was, of course, organized and encouraged from Madrid and supported by the city of San Sebastián -the hometown of Fermín Lasala y Collado- and the rest of the basque provinces. More than thousand men were called to arms by the city hall, the duke, besides his paper in the spanish Parliament as guipuzcoan deputy before the court of Madrid, gave money to enlist at least five men for the levy made by the San Sebastián town council to complete the guipuzcoan volunteer Tercio, wich, sent to Africa with two other raised by the provinces of Biscay and Alava, and joined to other spanish troops, fought gloriously in the battle of Wad-Ras. One of the various military operations that opened the doors of Northern Morocco, specially the strategic city of Tetuan, to the absolute and supreme international law of those days: the spanish guns, rifles, revolvers and bayonets. Then, it is not difficult to imagine that the Tamsamanni manuscript was, simply, war booty sent as a tribute to one of the most conspicuous promoters of that new spanish imperial expedition.

What about other possible explanations? Well, Fermín Lasala y Collado was the classical nineteenth-century political patron. Hundreds came before his doors asking for protection before that Power with capital “P” that he represented, used and owned.

Muhammad al Tammsamani have a deep problem as other little letter included in the manuscript explained: his father was prisoner of the alaui empire. Was, in fact, that precious manuscript, a literary jewel, a token offered to the only power, backed by modern artillery and thousands of bayonets, wich, logically, can compel the alauis to free his father?. San Sebastian city museum. Cristina Brunetti, duchess of Mandas. Portrait by Palmaroli.

The secretary of “Al-Andalus” did not told nothing about this, but he analyzed the manuscript only as a philologist, ignoring its historical context and the rol played by different historical characters as the duke, Muhammad al Tamsammani or the cruel, but defeated, alauis. The manuscript was, indeed, designed from the first to the last page, as a machinery -or a complex jewel- consacrated to obtain pardon, to implore help and mercy from powerful hands… perhaps only a mere coincidence? Anyway one thing was quite clear in this business: that year of 1862 Fermín Lasala y Collado and the state he represented have conquered the beach-head that forged the spanish empire in North and East Africa. More than fifty years after, from 1900 to 1905, the duke, the happy husband of the beautiful Cristina, was spanish ambassador before London. There, under the protective shadow of british power, he won finally a delicious lot in Africa for Spain, contributing to overwhelm any “native” resistance. For example the one organized around that sheik El Raisouli who John Milius transformed into a film character in the year 1975. So, as in Artigat, “interesting things” -enough “interesting” to become a movie- happened to the city siege of the Film Festival and its inhabitants before the coming of our boring, usually calm, days, when the only “interesting things” you can experience are featured in the movies… or hidden in forgotten archives.