|

This

is an interview extracted from Newsletter, a publication

of the Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada,

Reno.

Our

gratitude to David Río and to all who work in the

Center for Basque Studies, specially to Jill Berner.

This

next interview is publicated here as a homage to Robert

Laxalt, who had a good and unceasing relationship with Eusko

Ikaskuntza-Basque Studies Society. |

In

this humble way Robert Laxalt used to define himself whenever

asked about his role in the expansion of Basque studies in the

United States or about his literary contributions to Basque culture.

This extreme humility was one of the features that most struck

me about Bob Laxalt when I first interviewed him in the spring

of 1995. At that time I was familiar with his impressive literary

career and admired him for his imaginative writings on the Basques.

In the following years, until our last meeting in September 2000,

I had the pleasure to visit Bob almost every summer and to discover

his deep humanity. Over time, my admiration for Bob Laxaltīs literary

gift was equaled by my high respect for his remarkable human values. In

this humble way Robert Laxalt used to define himself whenever

asked about his role in the expansion of Basque studies in the

United States or about his literary contributions to Basque culture.

This extreme humility was one of the features that most struck

me about Bob Laxalt when I first interviewed him in the spring

of 1995. At that time I was familiar with his impressive literary

career and admired him for his imaginative writings on the Basques.

In the following years, until our last meeting in September 2000,

I had the pleasure to visit Bob almost every summer and to discover

his deep humanity. Over time, my admiration for Bob Laxaltīs literary

gift was equaled by my high respect for his remarkable human values.

During these long

interviews with Bob Laxalt I was primarily interested in his Basque

roots and, above all, in his creative writings on the Basques.

In considering his work, we cannot forget that Bob Laxalt was

not just "a Basque who wrote", but the voice of Basque

immigrants in the United States, as exemplified in his masterpiece

"Sweet Promised Land" (1957) and in his superb trilogy

of the Indart family, which was composed of the novels "The

Basque Hotel" (1989), "Child of the Holy Ghost"

(1992) and "The Governorís Mansion" (1994). Likewise,

he displayed a similar artistic power when portraying the traditional

lifestyle of the Basque Country in  non-fiction

books such as "In a Hundred Graves: A Basque Portrait"

(1972), "A time We Knew: Images of Yesterday in the Basque

Homeland" (1990) or "The Land of My Fathers: A Sonís

Return to the Basque Country" (1999), and also in the novella

"A Cup of Tea in Pamplona" (1985). In fact, Robert Laxalt

may be regarded as the most talented American author writing on

the experience of Basques both in America and in Euskal Herria. non-fiction

books such as "In a Hundred Graves: A Basque Portrait"

(1972), "A time We Knew: Images of Yesterday in the Basque

Homeland" (1990) or "The Land of My Fathers: A Sonís

Return to the Basque Country" (1999), and also in the novella

"A Cup of Tea in Pamplona" (1985). In fact, Robert Laxalt

may be regarded as the most talented American author writing on

the experience of Basques both in America and in Euskal Herria.

In spite of my

interest in Laxaltīs impressive achievements as a literary interpreter

of the Basques, Bobís characteristic modesty sometimes prevented

him from expanding on his writing. I remember that during these

long interviews he would tell me from time to time: "Just

let my works speak for themselves!". However, it was so interesting

to hear about both his Basque roots and his literary production

that I evaded his request and we went on talking for hours on

these topics. The following passages are an extract from one of

our talks of 1995. They summarize both his intimate connection

with the land of his ancestors and his literary commitment to

offer an honest portrait of the Basques.

-Mr. Laxalt,

could you start by describing your Basque roots and the early

experience of your family in the United States?

Well, when I went with

my father to the Basque Country, back in the 1950s, I was totally

surprised, I didnít know anything about the Basque Country, nothing

about its history or culture. However, my first language was Basque.

My brother Paul and I spoke Basque while we lived on the Basque

ranches. But when we moved to Carson City and went to school,

none of the other children spoke Basque, so we had to leave it.

And it wasnít fashionable to be ethnic. Now. It is, but then it

wasnít. So we forgot Basque as quickly as possible.

-When

did you start to explore your Basque roots? -When

did you start to explore your Basque roots?

When I went with Papa

to de Basque Country, I fell in love with the place. I couldnít

imagine anybody leaving such a beautiful country. I didnít take

any consideration at all because most of them were poor and they

had no opportunities there. But I had been raised in the desert,

so I was totally in a trance when I arrived there. I couldnít

believe it. I was feeling that I had always been there. It was

just somewhere in my folk memory. Besides, the people in the Basque

Country were beautiful people. I never felt alienated there at

all. They were my kind of people: they were strong and forthright.

The second time we went there, I missed it so badly that, when

we got to Garazi, I cried. I donít cry very easily. I just loved

the country.

-When and why

did you think that the Basque Country end the experience of Basque

immigrants in the United States could attract the interest of

the American audience? In Fact, your first book, "Violent

Land: tales the Old Timers Tell" (1953), does not deal with

this subject.

Oh, no, and itís the

same with A Lean Year and Other Stories (1994). Most of

those arenít Basque, they are American. It wasnít until Sweet

Promised Land that I started my Basque period, but it was

difficult to convince publishers in New York that the Basques

were something worthy to write about. Publishers only thought

about money and market and there werenít many Basques around.

So I was discouraged. At first, I couldnít understand why they

werenít interested in Basque things. Then, however, as Bill Douglass

pointed out, this worked to my advantage because Sweet Promised

Land became an immigrant book. It was not particularly a Basque

book because I didnít know so much about the Basques. But that

book attracted so much attention that it opened up a whole new

field and other Basques began to write, and non-Basques began

to write, too.

-Do you think

that the key factor for the success of "Sweet Promised Land"

was the fact that it is not a novel, but a non-fiction story,

told in an intimate, personal style?

I

never analyzed why it was successful. It came as a shock to me.

I tried for a year to start that book. Finally, when I started

to write it, I was ready to give up. I couldnít write it as a

novel because something was missing. I think that the poignancy

of the trip to the Basque Country moved me very much. I guess

that it was a story of discovery for me too, but I never went

in that direction because it was my fathers story. Then I said

I would try one more time and I took the paper and the typewriter.

I wasnít even thinking and I wrote: "My father was a sheepherder

and his home was the hills". Then when I wrote that one line

and I did realize what Iīd written, I knew that I got the book. I

never analyzed why it was successful. It came as a shock to me.

I tried for a year to start that book. Finally, when I started

to write it, I was ready to give up. I couldnít write it as a

novel because something was missing. I think that the poignancy

of the trip to the Basque Country moved me very much. I guess

that it was a story of discovery for me too, but I never went

in that direction because it was my fathers story. Then I said

I would try one more time and I took the paper and the typewriter.

I wasnít even thinking and I wrote: "My father was a sheepherder

and his home was the hills". Then when I wrote that one line

and I did realize what Iīd written, I knew that I got the book.

-What was the

general reaction of readers toward "Sweet Promised Land"?

Can we talk about a more favorable response by the immigrant groups,

particularly the Basque community in the United States?

Well, first the critics.

There was a massive amounts of reviews. They came here from everywhere,

New York Times and others. And then England picked it up.

I never expected that. And about the reaction of the Basque-Americans,

at first I was apprehensive about my father. But their response

was amazing. Other immigrants also liked the book, but the Basque

ĖAmericans really loved it.

-You said once,

"Itís a very difficult thing to write about the Basques or

any other nationality unless youíve seen them in their own land".

What was the influence on your work of your different trips to

the Basque Country?

I knew the Basques

here, but there was always something missing in the Basques that

I knew in this country. The cycle wasnít complete. There was something

in seeing them on their own land and with their own people, as

I could see in my two years over there. I saw their reactions

and I saw how differently they reacted here. Here they always

seem like other immigrants that react almost as if they didnít

belong here. And when you think about it, they donít.

-Most of your

books show a positive image of the Basque Country, even an idyllic

one, except perhaps "A Cup of Tea in Pamplona" and "Child

of the Holy Ghost". Do you agree with this?

Oh,

I tried to be honest when writing about the Basque Country. Well,

Child of the Holy Ghost was written because I was really

triggered by what happened to my mother there. I genuinely felt

it. I didnít try to portray the village as cruel. I was just the

way things were. In a way that was good for me because it gave

me objectivity. I could see that there could also be cruelty and

then I remembered all those wonderful movies about incidents in

England and Ireland and the cruelty of village life. So it worked.

And A Cup of Tea in Pamplona was a real thing in the sense

that i saw people there being denied an opportunity, poverty...Itís

an honest view. I love the Basque Country and the Basque people,

but that does not deny me the right to say when theyíre wrong.

Otherwise, I couldnít be honest. Oh,

I tried to be honest when writing about the Basque Country. Well,

Child of the Holy Ghost was written because I was really

triggered by what happened to my mother there. I genuinely felt

it. I didnít try to portray the village as cruel. I was just the

way things were. In a way that was good for me because it gave

me objectivity. I could see that there could also be cruelty and

then I remembered all those wonderful movies about incidents in

England and Ireland and the cruelty of village life. So it worked.

And A Cup of Tea in Pamplona was a real thing in the sense

that i saw people there being denied an opportunity, poverty...Itís

an honest view. I love the Basque Country and the Basque people,

but that does not deny me the right to say when theyíre wrong.

Otherwise, I couldnít be honest.

-Finally, what

do you think about the future of literature about Basques written

by the new generation of Basque-Americans?

I canít really predict

the future generationsī attitude. More and more the youngest seem

to be interested in their heritage. Monique [Laxalt, Robertís

daughter], for example, has identity with the Basque people and

the Basque Country, and she can write very well. And there are

others who might do it for some old, romantic, exotic sense, but

on the whole I cannot tell. I canít predict because being in love

with ancestors happens in some people and doesnít happen in others.

But as long as you have writers like Monique- and she is an honest

writer- I guess you can be optimistic about the future.

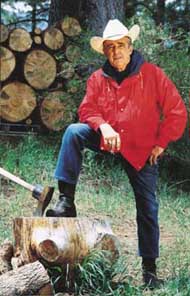

Robert Laxalt

and David Río at Bob's house near Carsan City, Nevada.

|

David

Río is a professor of American Literature at

the University of the Basque Country in Vitoria. He wrote

foreword to the Spanish edition of "Sweet Promised

Land: Dulce Tierra Prometida", recently published in

Spain by Ttarttalo.

Author Robert

Laxalt, son of Basque immigrants, died March 23 in Reno,

Nevada, a t the age of 77. Laxalt had been Director of the

University of Nevada Press since its beginning in 1961 until

his retirement in 1983, and was instrumental in forming

the Center for Basque Studies.

At a memorial

service on March 28, former UNR President Joe Crowley called

Laxalt "one of Nevadaís greatest authors", and

said that "the University was privileged to have him

for many years as one of our leading citizens-as creative

administrator, a teacher of writing, a lover of books, a

friend to students and colleagues". He impressed students

in his writing classes with his encouragement and expertise,

and his ability to guide them in finding their personal

writing style. Many of his internationally acclaimed books

were included in the Basque Book Series published by the

University of Nevada Press, including "In a Hundred

Graves: A Basque Portrait" (1972), "The Basque

Hotel" (1989), and "A time We Knew: Images of

Yesterday in the Basque Homeland"(1990). "Sweet

Promised Land", first published in 1957, established

him as an expert on Basque culture and as a spokesperson

for Basque Americans.

In 1986,

Laxalt was awarded the Tambor de Oro (Golden Drum Award)

by the city of San Sebastián, Spain for his contributions

to the Basques and spreading their culture. He received

many other honors throughout his career, and was twice nominated

for a Pulitzer Prize in fiction. He has been lauded for

his many contributions to the University and to the state

of Nevada.

Robert Laxalt

will be greatly missed by all who knew him. Goian bego,

Robert. |

Photos: John Ries, "Nevada

Appeal" and Joyce Laxalt

Euskonews & Media 132.zbk

(2001 / 7 / 20-27)

|